Akong Rinpoché Establishing Buddha-Dharma

Part Sixteen: Establishing the Kagyu Mahamudra Trainings ....Part 2

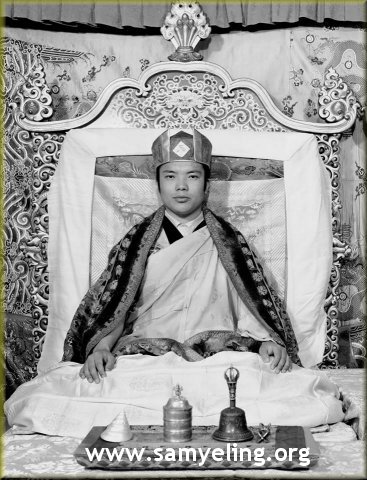

In the 1980s the connection between the XIIth Tai Situpa and Akong Rinpoché deepened and deepened, as the Tai Situpa devoted much of his precious time to visiting Samye Ling to teach. Akong Rinpoché had also accompanied him to Tibet on the Situpa's first, epic visit there in 1985.

In the 1980s the connection between the XIIth Tai Situpa and Akong Rinpoché deepened and deepened, as the Tai Situpa devoted much of his precious time to visiting Samye Ling to teach. Akong Rinpoché had also accompanied him to Tibet on the Situpa's first, epic visit there in 1985.

Following much discussion between them and in response to Akong Rinpoché’s earnest request, the Tai Situpa committed, in the 1990s, to teach Mahamudra publicly, as meditation practice instructions, in Samye Ling, basing his teaching on the text Mahamudra, Ocean of Certainty. There were to be strict requirements asked of those following these teachings and the training would be based on a yearly course at Samye Ling, during which time practice instructions for the coming year would be given, along with a schedule. The Tai Situpa also agreed to direct the students through personal interviews, supervising their progress.

This idea crystallised into a plan for two courses—a five-year programme and a seven-year programme—thereby making the course available to those with more time or less time available in their lives for practice. The training would take people, as a group, through the shamatha and vipasyana exercises of the text up to the stage of “pointing out”, ifthe candidate was deemed ready (Tai Situpa would decide that). Those who were ready would receive and then continue their practice individually, as group training from that point onwards made little sense.

The Tai Situpa taught Mahamudra successfully according to this plan, from 1989 through to 1997. The five-year group completed but the seven-year group could not finish as planned, because travel document difficulties prevented the Tai Situpa from leaving India. They (or many of them, at least) eventually did complete some twelve years later, but in India, going in group to Sherab Ling in 1996 and 1997 for the two final years of their training. Himself unable to leave India, the Tai Situpa had set up a Mahamudra training in Sherab Ling for his non-Tibetan students and the seven-year Samye Ling group was able to complete its training by piggy-backing one of these groups.

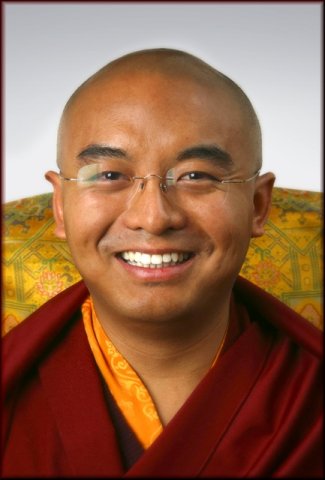

With the Tai Situpa no longer able to return to Samye Ling, Yongey Mingyur Rinpoché was requested by him and by Akong Rinpoché to teach Mahamudra in the West. Mingyur Rinpoché made a three-year programme for doing this. This proved helpful for many people but Akong Rinpoché, observing the students and the rather light way they were using these teachings, found it not as adequate as the Tai

Situpa’s training, along with its larger commitments, had been. He found no problem at all with Yongey Mingyur Rinpoché’s teaching. He was very happy with that and full of respect for such a great master: very glad to have him make such a positive connection with Samye Ling, despite the many calls on his time from his own growing organisation.

With the Tai Situpa no longer able to return to Samye Ling, Yongey Mingyur Rinpoché was requested by him and by Akong Rinpoché to teach Mahamudra in the West. Mingyur Rinpoché made a three-year programme for doing this. This proved helpful for many people but Akong Rinpoché, observing the students and the rather light way they were using these teachings, found it not as adequate as the Tai

Situpa’s training, along with its larger commitments, had been. He found no problem at all with Yongey Mingyur Rinpoché’s teaching. He was very happy with that and full of respect for such a great master: very glad to have him make such a positive connection with Samye Ling, despite the many calls on his time from his own growing organisation.

After Mingyur Rinpoche's teachings were completed and he was no longer available to lead future courses, Akong Rinpoche next vigiously encouraged any of his disciples who could manage it to attend the Mahamudra trainings being given by the Tai Situpa in India in the 2000s, saying:

“You are the most lucky people in the whole world. The Tai Situpa has become the main lineage-holder for our Karma Kamtsang tradition and is our greatest living guru, the highest holder of Mahamudra. There is no one better to receive these precious transmissions from. I myself would love to receive these teachings from him but circumstances do not allow. You are all far more fortunate than I am. Not just that... the whole reason that the Gyalwa Karmapa escaped from Tibet to India and risked everything was for one purpose, one reason only, and that was to receive this Mahamudra transmission from his guru, the Tai Situpa. You will have the opportunity to receive the same thing as the Karmapa does, the deepest treasure of our lineage. You should really appreciate this and do everything you possibly can to learn these teachings properly and to practice them as he tells you.”

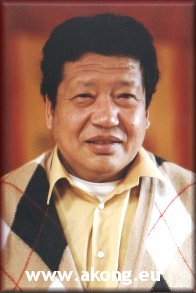

Groups from Samye Ling and the various Samye Dzongs—some relatively large ones from Brussels and London—did attend these teachings. Rinpoché was pleased with that but also, as time went by, became again disappointed [1] by the lack of impact on many of the students of even the Tai Situpa’s Mahamudra teachings, so perfect in themselves. It seemed obvious to him that either people were not putting in enough hours of practice for each step of the training or else that they lacked the renunciation and devotion that are the vital prerequisites for Mahamudra meditation to work. Probably both factors were present. He was rather saddened by the way in which, in some places, the Mahamudra students deserted the very centres through which they had linked up with dharma and Mahamudra, and became either a group apart or simply individuals practising alone, disconnected from their dharma roots. On more than one occasion Rinpoché told them in no mean terms how now was the time to pay back the kindness from which they had benefited and to actively help the centre.

In many cases, his words fell on deaf ears. He had spent his life making it possible for Westerners to get access to one of the very finest jewels humanity has ever encountered ... but found that the jewel—Mahamudra—was being treated just like anything else because most of the students had not yet “tasted” the real thing. A new development in 2008 revived Rinpoché’s hopes for people to gain authentic realisation of Mahamudra: the advent in Scotland of Khenpo Lhabu, now widely known through his title of Druppon Rinpoché. Akong Rinpoché’s nephew, Tsultrim Palbar, had been studying in Thrangu Rinpoché’s monastery in Nepal and had then entered the long retreat there, directed by Khenpo Lhabu, who had subsequently become his own guru. Through his own success in retreat, Tsultrim Palbar became, at Akong Rinpoché’s request, appointed as “Kating Lama” by Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoché and was being groomed to be the future abbot for Samye Ling.

Kating Lama wanted very much for Khenpo Lhabu, Druppon Rinpoché, to come to Scotland, for his own and everyone’s benefit and Akong Rinpoché recognised the great benefits this could have, as Druppon Rinpoche had so many qualities. In particular, he was known as a very gifted master of Mahamudra, a possessor of a very direct Mahamudra meditation method of questioning-and-cornering that enabled suitable disciples to progress very rapidly. He was also a master of tap-lam. He was requested to take charge of the long retreats on Holy Isle and Arran, which he did, even though when he first came they were nearing their end. Most importantly, he was asked to take charge of subsequent long retreats and to teach the retreatants Mahamudra alongside their tap-lam training. Just as Akong Rinpoché had vigorously encouraged people to attend the Tai Situ Mahamudra, so also did he encourage them to attend Druppon Rinpoché’s teachings, knowing him to be one of the rare, 100% authentic and very gifted lamas of our time.

Sadly, Rinpoché’s passing happened before the end of the 2011-2014 retreats and he is not there to see the outcome of his efforts to place its retreatants in the presence of such a well-endowed teacher. In the Foreword, it was mentioned that ston pa means one who teaches but also one who shows. Although Akong Rinpoché did teach Mahamudra to some people personally and also gave one public

course based on sections of Mahamudra, Ocean of Certainty, he was not known publicly as a "teacher of Mahamudra", in the sense of giving formal instruction. By contrast, his life day after day was one, non-stop, living example of Mahamudra being practised. The way in which he moved, spoke and so forth was the textbook example of Mahamudra mindfulness. The Tai Situpa said that Rinpoché had a very high level of attainment indeed, demonstrated by his being

able to go hour after hour, day after day, week after week, in a state of Mahamudra, without ever "needing time out, to recover”...”as I do,” smiled Tai Situpa. Rinpoché remained constantly centred in deepest truth, never leaving the primordial space of dharmakaya no matter what he did on the surface.

Sadly, Rinpoché’s passing happened before the end of the 2011-2014 retreats and he is not there to see the outcome of his efforts to place its retreatants in the presence of such a well-endowed teacher. In the Foreword, it was mentioned that ston pa means one who teaches but also one who shows. Although Akong Rinpoché did teach Mahamudra to some people personally and also gave one public

course based on sections of Mahamudra, Ocean of Certainty, he was not known publicly as a "teacher of Mahamudra", in the sense of giving formal instruction. By contrast, his life day after day was one, non-stop, living example of Mahamudra being practised. The way in which he moved, spoke and so forth was the textbook example of Mahamudra mindfulness. The Tai Situpa said that Rinpoché had a very high level of attainment indeed, demonstrated by his being

able to go hour after hour, day after day, week after week, in a state of Mahamudra, without ever "needing time out, to recover”...”as I do,” smiled Tai Situpa. Rinpoché remained constantly centred in deepest truth, never leaving the primordial space of dharmakaya no matter what he did on the surface.

[1] It is sometimes strange to use terms like « disappointed » or « hopeful » in respect of an enlightened mind such as Rinpoché’s, so much beyond hope and fear, yet nevertheless, to all intents and purposes he displayed those reactions and also explained them through discourse.

.....this narrative continues: Establishing Tap-Lam, the Long Retreats