Akong Rinpoché Establishing Buddha-Dharma

Part Eighteen. Establishing Tap-Lam, the Long Retreats ....Part 2

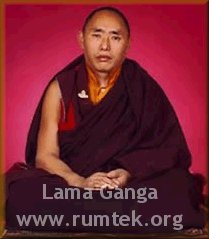

A long retreat requires three essential things: a retreat-master, suitable retreatants and a suitable property, with shrine room and yoga room. The search for a good retreat-master was solved by Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoché, who told Akong Rinpoché that he (KTR), Khenpo Karthar(who was in the New York KTD) and a certain Lama Ganga were three close friends, all born in the same year and that Lama Ganga was perfectly qualified to be our retreat master. Akong Rinpoché therefore approached Lama Ganga, who, with a little encouragement from Thrangu Rinpoché, eventually agreed to lead the Samye Ling retreat and to visit Samye Ling prior to the retreat to give teachings to prepare the future retreaters.

A long retreat requires three essential things: a retreat-master, suitable retreatants and a suitable property, with shrine room and yoga room. The search for a good retreat-master was solved by Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoché, who told Akong Rinpoché that he (KTR), Khenpo Karthar(who was in the New York KTD) and a certain Lama Ganga were three close friends, all born in the same year and that Lama Ganga was perfectly qualified to be our retreat master. Akong Rinpoché therefore approached Lama Ganga, who, with a little encouragement from Thrangu Rinpoché, eventually agreed to lead the Samye Ling retreat and to visit Samye Ling prior to the retreat to give teachings to prepare the future retreaters.

In 1981 Akong Rinpoché announced that Samye Ling’s first long retreat would start in 1984 and that training for it would start that year. The actual retreaters were to be selected from the broader Samye Ling community of Akong Rinpoché’s students. The building was self-build by Samye Ling staff and taking part in its construction would be part of the preparation that the future retreaters had to do. The building was happening at the same time as that of the Samye Temple and the retreatant’s participation was vital so as not to draw too many building staff away from that main project. Akong Rinpoché very actively participated in the building work for the retreat, setting a high and enthusiastic pace and, of course, blessing the whole site by his input.

By the end of 1982, the main retreat candidates were chosen. As one of them, I attended the meetings between them and Akong Rinpoché. He insisted, among other things, on the whole vision of retreat as being one of humility and not as one of a raise in status. Rinpoché was not happy with the way in which those who had completed the first Kalu Rinpoché retreat had, simply through that fact, all started styling themselves “lamas”, whether they had realisation or not and no matter what had happened in the retreat . He explained that, although it was very tempting for people to carry the title “lama”, they had misunderstood Kalu Rinpoché who, in Vajradhara Ling , had said that those who had been successful in the retreat and who remained as ordained sangha afterwards could call themselves “lama” if they wished. Those who returned to a lay life might call themselves “yogi” (naljorpa). This, Rinpoché explained, was not the traditional Tibetan system but done to encourage people. He seemd to have found that in most cases this was an obstacle rather a help, because it inflated people’s egos rather than helped diminish them. He told the future Samye Ling retreaters, with tears in his eyes:

“When you come out of retreat you should wish to be the lowest of the low: to be like a broom, the lowliest of objects that deals with all the dirty things but really helps people. If ever I hear of any of you calling yourself “lama” after the retreat, I don’t want to know you any more; you are nothing to do with me. I want that to be very clear. Retreat is there to make you humble, no longer concerned for yourself but only caring for others!”

“When you come out of retreat you should wish to be the lowest of the low: to be like a broom, the lowliest of objects that deals with all the dirty things but really helps people. If ever I hear of any of you calling yourself “lama” after the retreat, I don’t want to know you any more; you are nothing to do with me. I want that to be very clear. Retreat is there to make you humble, no longer concerned for yourself but only caring for others!”

The dharma visits of the Goshir Gyaltsabpa, Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoché and Khenpo Tsultrim Gyamtso in 1982 and 1983 covered much of the initial training Rinpoché had envisaged for retreaters (see page on this programme). Lama Ganga almost never made it to Scotland, being held in Prestwick airport for many hours into the night due to irregularities in his papers and visa. I had gone to collect him and was allowed to stay with him in custody as his interpreter. He started saying, “I obviously don’t have a karmic connection with this. No problem, I’ll just go to India. Tell them not to bother.” He was very easy-come, easy-go for those sorts of things and there was a real danger he would pull out altogether. After redoubled efforts and phone calls to the night staff at the Home Office, he was allowed in. Akong Rinpoché told me we had been lucky, as Lama Ganga was the sort of person to have just dropped the project there and then, because the signs were not good.

Lama Ganga continued the training for the retreaters and the building work on the retreats progressed. All was in order but in the meantime a new project emerged for Rinpoché.In the early 1980s, Tibet started opening up for the first time since the Cultural Revolution. Akong Rinpoché made his first return to his homeland and to Dolma Lhakang in 1983, returning with the skulls of his parents that the people back home had kept for him, should he ever return. The Tai Situpa, with whom Rinpoché had a growing connection, wanted Akong Rinpoché to both help organise a return trip for him, to his seat at Palpung, and also to accompany him. His return would be a major event and the tai Situpa would be the highest-ranking lama to return to Tibet since the flight of the Dalai Lama in 1959. The Situpa wanted Akong Rinpoché to negotiate all of that with the Chinese authorities. Akong Rinpoché estimated the whole trip may last for some three months or more and he told me that he did not want to leave Samye Ling for that long without either him or myself to “care for it”. He said that I may have to await his return before going into the retreat, that was due to start during his projected absence, but that I could “go in late and catch up, as you’ve already done the Foundations.”

As it happened, the negotiations took far longer than anticipated and the retreat started with Akong Rinpoché still in Scotland. I visited the retreat daily, to give Tibetan classes and to spend a moment in my room, awaiting my entrance in months to come. At first I was to enter the retreat three months late, then six months late, then nine months. By some eight or nine months into the retreat, all the visas and permissions and planning for the Tai Situpa visit were at last in place but once Akong Rinpoché’s return was past the one-year mark of the retreat, and the start of the Vajravarahi practice, he took me for a long walk and explained that he was really, really sorry but it would now be too late to enter the retreat and he really needed me there in Samye Ling during his absence, to manage it, materially and to some extent spiritually, dealing with people’s practice difficulties. He was so apologetic that it was embarrassing. I explained to him that it mattered less for me, as he had already been so kind in teaching me Mahamudra and that I was therefore not desperate for the retreat practices. He said that was true but that nevertheless it would be good to do the retreat practices as well and that he would guarantee that, no matter what, I would enter the next retreat, programmed for 1988: third time lucky !

When there is a lifetime acquaintanceship, like that with Rinpoché, there are always somehow a few snapshot moments that stand out as landmark memories and flag themselves up first whenever one strolls down memory lane. That walk, Rinpoché’s concern for me and my spiritual progress, his kindness and his obvious discomfort that I should “suffer” in order to make his project work ... all of that was one of the first moments of intimacy with him, outside of the usual role-play of guru and disciple that is automatically generated by the disciple situation.

Akong Rinpoché treasured meditation very much and would always encourage people to practice it. Once, walking with him by the Esk river, he made us both take a significant detour simply so as not to risk distracting a person who was meditating by the water’s edge.

The next episode in the development of the retreats involves the complex role of Akong Rinpoché in the life of his brother, originally Jamdrak and now Lama Yeshe Losal Rinpoché (LYR), a story explored briefly, in its own right, elsewhere on this site. They had a sibling, Palden, who had remained in Tibet and suffered greatly in prison, where he had been physically damaged. He had poor health. On his return journeys to Tibet, Akong Rinpoché had met his now-freed brother and wanted to bring him to Scotland, to visit, along with a sister, Simi. Visas for the UK were eventually obtained but it was not possible to get him a USA visa to visit brother Jamdrak (LYR). Who can say how much Akong Rinpoché sensed of the future role for brother Jamdrak but the outcome of the situation was, that for all of Akong Rinpoché’s respect for retreat, he told his brother that if he wanted to see Palden while he was still alive, the only option would be for him to leave his closed retreat in Woodstock, USA, at the Karma Triyana centre, and to continue it in Scotland, where his brother Palden and sister Simi would be. Akong Rinpoché felt that Palden had suffered partly simply because of being his brother and he was somehow indebted to him. He put considerable pressure on Yeshe Losal to come.

The latter had made a personal commitment to spend twenty years in strict retreat so the decision was not an easy one for him. In the end, he took up Rinpoché’s suggestion and returned to Scotland, installed in the septagonal house at Pureland, in 1985. Lama Ganga, who had presaged his own death, wanted to die in Tibet and so returned there to pass away in 1988. With no obvious successor to replace him, Akong Rinpoché asked his brother to take charge of the next retreat, staring in 1988. With the acquisition of Holy Island—Lama Yeshe Losal’s project—and the later acquisition of Glenscorradale farm on Arran (which became the men’s retreat), the story of the retreats continues mainly under Lama yeshe’s inspiration and guidance, as well as that of Ani Zangmo, later to become Lama Zangmo. Akong Rinpoché remained nevertheless deeply involved with the spiritual care of the retreatants and with any major decisions concerning the retreats, until his passing.

By the way, when the time for the 1988 retreat came—my "third time lucky—Rinpoché and I both concluded I was of more use to him, to Samye Ling and to the world continuing my teaching work. We decided that life itself would be my never-ending retreat-cell.