The Oxford Years

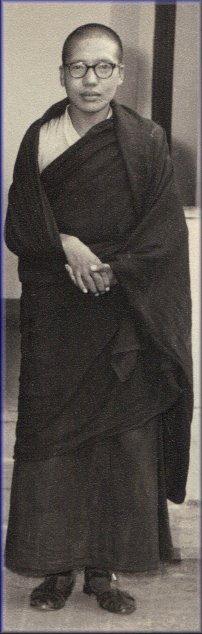

At first, Akong Rinpoché and Trungpa Rinpoché were lodged with a kind host, giving them the time to find their feet in this new land and new culture, different again from that of India and of Tibet. Rinpoché described the journey from Tibet to the UK as being like time travel. As the months went by, they wanted more independence and Akong Rinpoché sought employment in order

to finance the simple lodgings they found. The lives of the two rinpochés diverged. Trungpa Rinpoché soon became a popular figure in Oxford and London and lived a life of networking, meeting followers of other spiritual paths, as well as Buddhists, and also one of discovering British culture and Western art. Chime Tulku also came to join them in the flat. Akong Rinpoché, who was looking after all three, had only been able to find work as a hospital porter. This was another formative moment

of his experience and one probably that helped later give rise

to the Tara therapy. In his own words:

At first, Akong Rinpoché and Trungpa Rinpoché were lodged with a kind host, giving them the time to find their feet in this new land and new culture, different again from that of India and of Tibet. Rinpoché described the journey from Tibet to the UK as being like time travel. As the months went by, they wanted more independence and Akong Rinpoché sought employment in order

to finance the simple lodgings they found. The lives of the two rinpochés diverged. Trungpa Rinpoché soon became a popular figure in Oxford and London and lived a life of networking, meeting followers of other spiritual paths, as well as Buddhists, and also one of discovering British culture and Western art. Chime Tulku also came to join them in the flat. Akong Rinpoché, who was looking after all three, had only been able to find work as a hospital porter. This was another formative moment

of his experience and one probably that helped later give rise

to the Tara therapy. In his own words:

“From there I went to England because a friend of ours (Freda Bedi) came from England and said it was a good place to go, so we went. Somebody sponsored us for the first year, but then the sponsorship money ran out so I had to look for a job. I had only two choices: a factory or a hospital. So I decided to work in a hospital. I got a job as a porter and that’s the first time in my life that I had a physical job. I had to push patients around the hospital, and I didn’t speak much English at that time. I had never done a job like this and the nurses in the hospital thought that I was quite a lazy person because I didn’t know how to push patients on the trolley. That gave me the most suffering, mental suffering, of my life because although I had experienced pain and suffering through losing everything as a refugee, actually when you are in that refugee state you don't expect to be a very happy person.

But when you work in a hospital, then you start remembering what you did, your job in Tibet: you sat on a throne, you gave orders to people, but in the hospital you have to take people’s orders. Also the porter department taught you all the nasty things: you have keep to a particular time, and if you work too hard they will say "stop, go slowly", because we all have to keep the same time. "I took 5 minutes, you must take 5 minutes. You are not allowed to be back in 3 minutes". So many rules and conditions. And for the first time I worked at manual labour and cleaning toilets, which in Tibet is something that would never happen for Lamas and Tulkus, not even in your imagination. So my mind tortured me for three years. [1]

But then during that time I was able to turn myself to the teachings I had received from my teachers, and I began accepting with tolerance, having patience, accepting whatever comes. Then you look at everything as beautiful and good, and you never look at things as being ugly or bad. So I survived because of my teachers and the advice they had given. I healed myself through my teachers. I saw many good people in England but I also saw many difficult people. We stayed in a lodging, bed and breakfast, and at that time a porter’s income was very little, and after you had paid for the rent and something to eat, there was nothing left. Even the food had to be very limited. For some years in Oxford my friend and I could only afford to eat a piece of bread and breast of lamb, because breast of lamb is something they throw away for the dogs. So you can buy five pence worth of breast of lamb, and you boil that and you put it on the bread in the morning: one in the daytime and one in the evening. That’s how I survived for three years.

And another thing, the person we were renting the room from, the owner of the room, was a very old lady, about 90. But there was a person who pretended that he was taking care of the property for her. He threatened us with a knife, quite a long knife, trying to increase the rent every week and saying "If you don’t pay, then this is what we are going to do". So sometimes we had a very hard life because we didn't actually know what we should pay, and if we paid everything then we had nothing to eat. But this was also a very valuable lesson for us. My teacher told me you cannot change the whole world. If you don’t like the world being full of stones, you can try to cover that whole world with a carpet, but that is not possible. You can walk if you find decent shoes. So you give up the idea of covering the whole world with a carpet, and instead you cover your feet so you can walk wherever you want.”

The intense suffering that Rinpoché describes seems to have lasted long enough for him to learn whatever he needed to learn from it. A more positive counterpart to this story happened when an eminent doctor at the hospital, Dr Bent Juel-Jensen noticed Rinpoché's unusual ethnic features and enquired about his origins. Hearing that this porter and sometimes toilet-cleaner was a Tibetan lama and one qualified in Tibetan traditional medicine, Dr Juel-Jensen took an interest in him and arranged for his job to be changed to that of theatre porter, enabling Rinpoché to sit at times in the observation gallery and observe surgery, something that Rinpoché had wanted very much to do.

[1] This period of suffering racial prejudice and humiliation, as well as hands-on experience of life doing menial work, was to have a profound influence on Rinpoché throughout his life.

......continue to the next part of the story: the Finding & Founding of Samye Ling