The Flight into Exile

The XVIth Gyalwang Karmapa had accompanied the XIVth Dalai Lama and other eminent Tibetans to Beijing, in 1954, at the demand of Mao. On his return to Tibet, the Karmapa sent advance word for Kagyu tulkus and abbots to gather at Palpung. Once there, the Karmapa enthroned the newly-found Tai Situpa and gave several months of ritual transmissions and teachings. It became known that during his visit, the Karmapa would give, as previous Karmapas had done, a once-in-a-lifetime transmission of rare Kagyu protector teachings to a select group of thirteen rinpochés. To the amazement of the almost one hundred reincarnate lamas gathered there, Akong Tulku, a relatively-unknown and unimportant lama, was one of those chosen. [1] Above all, the Karmapa gave the advice that it would be necessary soon to flee Tibet as there was no hope of a positive outcome in the present situation. Soon afterwards, Akong Rinpoché returned to Dolma Lhakang, informed his people of the Karmapa’s terrible news and predictions.

These were confirmed in the following years by the arrival or more and more Chinese troops and their eventual advance through Eastern Tibet. In the year of 1958 and early 1959 there were various signs, such as statues bleeding, temple pillars cracking and an absence of flowers in the fields had led people to expect something terrible. At Akong Rinpoché’s request, his younger brother, Jamphel Drakpa (“Jamdrak”) had been brought from the family home to join him at Dolma Lhakang. Rinpoché wanted him to have good prospects for the future and thought it best he train to be a secretary/personal assistant to a high lama and so he was taught the necessary skills. Akong Rinpoché and his brother joined the fleeing group of Trungpa Rinpoché and Yag Tulku. In his own words:

“When I was eighteen or nineteen all Tibetans had to decide whether to stay or go so we decided to leave in 1959. The population of Tibet was six million, and one million Tibetans left and went to India. Out of the one million that left between 1959 and 1960, eighty thousand people reached India. Our journey took ten months. I can only tell the story of my group. In the beginning there were three hundred people in our group and we travelled with horses and mules for four months. Then the Chinese took over Lhasa, the capital of Tibet and as I come from the eastern part of Tibet this meant that the borders into Tibet were closed.

So we had to cross from near Burma into India [2], and there is no way we could get horses or mules across, so we tried to escape by walking, and that took six months. Our group started as three hundred people, but only thirteen reached India after six months. So that was our group - the number that were able to get through. Now our group, the thirteen

people who survived, all had very good teachers, Tibetan Buddhist teachers. Every one of us remembered loving kindness and compassion, tolerance, forgiveness and not seeking revenge. So when you ask me about healing, I found that those teachings gave me the power of mind to survive, because if we had not received those teachings I don’t think any of us would have lived. But not only that... When we had nothing to eat, many people died. We had to eat everything that we could. When things run out, there is a decision

to make. Shall we kill anything which is edible? Shall we eat somebody who dies first? Those are the questions and those are the decisions that we had to make. I don’t think anybody minded eating each other if the person was dead.

So we had to cross from near Burma into India [2], and there is no way we could get horses or mules across, so we tried to escape by walking, and that took six months. Our group started as three hundred people, but only thirteen reached India after six months. So that was our group - the number that were able to get through. Now our group, the thirteen

people who survived, all had very good teachers, Tibetan Buddhist teachers. Every one of us remembered loving kindness and compassion, tolerance, forgiveness and not seeking revenge. So when you ask me about healing, I found that those teachings gave me the power of mind to survive, because if we had not received those teachings I don’t think any of us would have lived. But not only that... When we had nothing to eat, many people died. We had to eat everything that we could. When things run out, there is a decision

to make. Shall we kill anything which is edible? Shall we eat somebody who dies first? Those are the questions and those are the decisions that we had to make. I don’t think anybody minded eating each other if the person was dead.

But people said we should kill animals, like rabbits for example, because we were going to die of starvation. Then the question arises: whose life should be lived, yours or the rabbit's? Why do you have the right to kill the rabbit in order for you to survive? So my decision was (and I do eat meat, don’t think I’m a very compassionate person, I do eat rabbit meat nowadays), but when it was a matter of survival, I made the decision that we would not kill the rabbits. If we are meant to die, we have to die. I do not see the difference between you and somebody else. But if one sees somebody dead, of course one would eat their body. There were people who did eat other people’s bodies, but not in our group because the people who were dead were dead in the snow, frozen. Some people, when they couldn’t walk any more, gave the food they had to us and said "you leave now, because in a matter of a few hours I am going to die anyway, so you go". They made their own decision.

So I feel that my teachers gave us the strength to be able to make our decisions. Now I very much appreciate my whole experience of escape, and how much suffering we went through. This was the best training of my life, because when I was in Tibet I didn’t really know what being poor meant, I didn't really know what a family’s suffering meant. Of course I hadn't had that kind of suffering, as I myself had never been starving. Therefore I expected everybody to be the same as me. But when I experienced all this, when I was close to death from starvation, I made the promise and decision that if I am still alive somehow by a miracle, if I am not dead today or tomorrow, I will not sit on a throne and teach, and have many servants, but I will become the servant of all suffering people, I will feed and educate them. [3] This is my commitment. I made my promise at that time. And luckily our group somehow managed to live. [4]

Then in a refugee camp in India we ate strange food for the first time, things which do not exist in Tibet and which nobody knew how to cook: onions, potatoes, tomatoes. All the vegetables were rotten and every day between thirty and forty people died due to tapeworms and roundworms. We stayed in India for three years and the exile government gave us jobs according to our education and qualifications. Most people were sent to work on the roads. All the Tulkus were sent for further education to learn the English language, but I myself did not have the chance to go to school. They put me in charge of managing the school and I was there for three years.” Following the advice of the Gyalwang Karmapa, a pattern was established here that was to be repeated later in Samye Ling, namely that Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoché was appointed Director of the Young Lamas Home School, in Dalhousie, and Akong Rinpoché was the Manager.

[1] This seems so significant in the light of Akong Rinpoché's later closeness with the XVIth Gyalwa Karmapa and his role in finding and instating the XVIIth. See relevant pages.

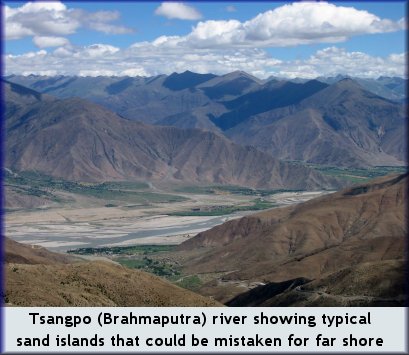

[2] At one point, the journey involved crossing the Tsangpo (Brahmaputra) river, in small coracles at night. They thought they had reached the far shore but in fact had only reached a sand island. Then they were detected and fired upon. They had to wade into the water to get to the far shore, soaked and then hide in the snow, banked up against a dead tree, in their wet clothes. Many were killed or captured.

[3] This was another profound influence on Rinpoché's later life, especially his Rokpa work.

[4] The thirteen people left were huddled in a cave, dying of starvation and too weak to move. They were just waiting for death. Fortunately, they were found by some hunters, who fed them sufficiently to enable them to make the last leg over the border.

continue to next episode: the journey west

r