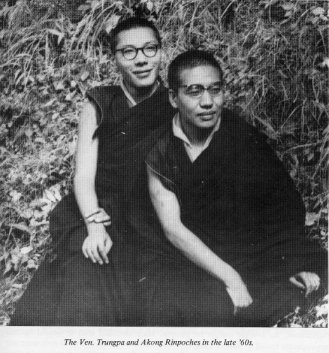

A Defining Moment: the Disagreement between Trungpa Rinpoché and Akong Rinpoché Concerning How the Teachings Should Be Given in Samyé Ling

The full story of what happened in the first two years at Samyé Ling and how the dissent developed will perhaps never come to light. The XVIth Gyalwang Karmapa, who arbitrated and decided the matter had sworn Akong Rinpoché to secrecy, instructing him to accept whatever other versions of the story might be told but, for many reasons, not to tell it in detail as it had actually

happened.

The full story of what happened in the first two years at Samyé Ling and how the dissent developed will perhaps never come to light. The XVIth Gyalwang Karmapa, who arbitrated and decided the matter had sworn Akong Rinpoché to secrecy, instructing him to accept whatever other versions of the story might be told but, for many reasons, not to tell it in detail as it had actually

happened.

In Akong Rinpoché’s own words, when I interviewed him on this subject were: “His Holiness said I should never tell, so my own lips are sealed!”

However, over the years, the topic did come up several times and key events happened which have given the author a fairly clear idea of what took place. When I ran my version of events past Rinpoché, he did not contest it in any way (taken by me as an implicit affirmation) and he simply again said how he personally was sworn to secrecy. Although, on one hand, that secrecy merited respect while Rinpoché was alive, the nature of what happened in that crucial period had such significance and ongoing impact on dharma in Europe

and in the USA, not to mention the impact on Akong Rinpoché’s own story, that perhaps now is the correct time to describe some of the relevant elements. Some justification for this came with Rinpoché’s own approval of a much-simplified version of events that I wrote in 2013 for inclusion in Naomi Levine’s book The Miraculous 16th Karmapa.

The propriety of Trungpa Rinpoché’s actions related to sex, alcohol and drugs, even in India and before Samyé Ling days, is not in question here nor was it at the time, directly. He was seen by some Tibetans, including Akong Rinpoché, as a mahasiddha and the latter are known for their sometimes unconventional Buddhist activity. Akong Rinpoché always spoke only respectfully of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoché as a person and a teacher. Their disagreement was about how to present Tibetan Buddhism at Samyé Ling, knowing that it was the first and only Tibetan centre in the West. Akong Rinpoché was for a classical approach, establishing traditional Tibetan studies, training in rituals and meditation and so forth. Trungpa Rinpoché—and most particularly after his return from a retreat in the Taktsang cave in Bhutan, where he had visionary revelations—wanted to modernise the Buddha’s message to suit Westerners and to tackle people in an unconventional and confrontational way that would break down their ego-barriers and not give them the excuse of formal religious structures in which to get lost. As one resident at the time said of him, “It was like being in the cage with the tiger!”

Trungpa Rinpoché willingly entered into the arena of drugs, drink and sex familiar to some of the visitors to Samyé Ling and met people there on their own ground. He also wanted the prayers to be done in English and composed new rituals in English. Akong Rinpoché was convinced that this was giving this new world entirely the wrong message about Tibetan Buddhism. He wanted people to start from the beginning and go through a progressive training—one based in the abstinence, moderation and precepts of the basic teachings of the Buddha and leading into the ways of the bodhisattva and, whenever and if ever the time would be right, the extraordinary path of the yogin. He also wanted to keep the Tibetan prayers and practices just as they had always been, among other things in order to preserve them in those difficult times when they might disappear forever. Yet Trungpa Rinpoché was not only his senior, within the Tibetan spiritual hierarchy, but also now a friend of many years with whom he had co-experienced discipleship of Shechen Kongtrul Rinpoché, the XVIth Karmapa and Khenpo Gangshar, flight from Tibet and near death, the Young Lamas School, the journey West and several years in Oxford.

It must have taken extraordinary courage to have confronted the powerful conviction driving Trungpa Rinpoché. However, with the intensifying of the situation, Akong Rinpoché became obliged to consider the duty he had as manager, appointed by the Karmapa, of Samyé Ling. Trungpa Rinpoché remained unwilling to listen to his reasoning and Akong Rinpoché realised that the only solution to their disagreement was to seek the Karmapa’s own opinion and arbitration. The XVIth Gyalwang Karmapa decided that although Trungpa Rinpoché may well act privately in the way he did, as a mahasiddha, it was not the right way to present the dharma in Europe and also not the way for an official Kagyu tulku to act in those circumstances, as it gave the wrong impression of the Kagyu lineage: a lineage that embraces the entire wealth of the Buddha’s teachings, for the millions, and not solely the way of the “crazy yogi”, for the very few. Therefore, Trungpa Rinpoché was to be disinvested of his Kagyu status if he insisted on continuing in the same way and he could, until further notice, not be considered to be acting as a Kagyu tulku. This decision by the Karmapa gave Akong Rinpoché the unenviable and most painful task of transmitting the Karmapa’s sacred instruction to his friend and companion.

.....continue reading the story of this parting of the ways here